The University of Worcester produces the Pollen Forecast for the whole of the UK in conjunction with the Met Office. Why do we get the dreaded hay fever?

Dr Beverley Adams-Groom, Chief Palynologist (pollen specialist) and Pollen Forecaster at the

School of Science and the Environment explains why we get hay fever and what we can do to monitor pollen.

Sneezy, Sleepy, Grumpy and Dopey – this is how you feel when you’ve got an attack of hay fever. Happy - when you haven’t got hay fever and, if you have it bad, you may need to see the Doc.

Hay fever is really no joke, though, being thoroughly debilitating and causing reduced quality of life, while going around with sore, red eyes is likely to make you Bashful. Approximately one fifth of the UK population are affected by hay fever, with more than three million affected by allergen-triggered asthma. The main culprits are pollen and fungal spores but the typical symptoms of sneezing, runny nose, itchy eyes and throat can be caused by many other triggers too, such as house dust mite faeces, pet fur and dander, cigarette smoke, scented candles, perfume, printer ink and cockroaches.

Pollen allergens are actually proteins embedded within the grains. When they hit onto the mast cells inside the nose, they trigger the release of histamine in sensitised individuals. Histamine is there to ward off invaders and its release causes itching, swelling, sneezing and mucous production – all those annoying symptoms which combine to make you feel like most of the seven dwarves rolled into one!

Only a few pollen types typically trigger hay fever because to get up a sufferer’s nose the pollen must be produced in high quantities and be able to get airborne easily. Grass pollen is the most common hay fever trigger in the UK, affecting around 95% of hay fever sufferers. Birch tree pollen is second, affecting around 25% of sufferers, followed by Oak, Alder, Hazel and a few others (no wonder Sneezy was snuffling – he lived in a forest surrounded by them!) These, very widespread, plants are pollinated by the wind and have small, light pollen that can easily become airborne. The flowers are indistinct on these plants – usually arranged on catkins dangling down, sometimes referred to as ‘lamb’s tails’.

Most flowers are pollinated by insects and have pollen that is textured and often sticky so that it can easily cling to the insects’ bodies and be distributed from flower to flower. Insect-pollinated pollen is usually heavy, produced in much lower quantities than wind-pollinated types and rarely becomes airborne. Many people suspect that oil-seed rape pollen causes their hay fever because they notice huge fields of bright yellow flowers. In fact it is usually birch or oak pollen that is causing their symptoms, which occur at the same time but are not all obvious.

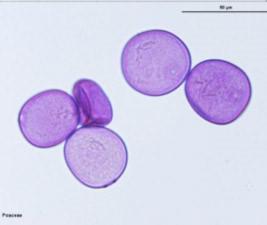

A collection of grass pollen grains through a microscope

A collection of grass pollen grains through a microscope

Pollen seasons are variable and therefore the production of pollen forecasts is important to enable sufferers to be prepared for the season. The amount of pollen produced and dispersed in any one season depends on a number of weather and climate variables, both pre-season and in-season. For example, a cold, dry spring will reduce the amount of grass pollen produced and also cause a late season onset, while a warm, wet spring will encourage high grass pollen production and an earlier onset. If we have high pollen production coupled with warm weather in-season, then pollen counts can be very high and hay fever sufferers will be very Sneezy and extremely Grumpy. Very wet summers lead to Happy hay fever sufferers since the pollen struggles to get airborne.

Current research is looking at ways of producing more detailed forecasts and real-time pollen monitoring:

Detailed forecasts: Until recently, grass pollen types (family or species) could not be separated from one another during pollen monitoring using microscopy because they are so morphologically similar. However, new DNA techniques are able to analyse the pollen in the air and determine when specific grass types are in season. Work is also ongoing to produce models for highly detailed pollen forecasts, something which is not currently available for the UK. This is all very useful because the type of grass to which individual sufferers are affected can vary substantially. Forecasting according to grass type allows sufferers to get to know which ones they are affected by. Similar work is also being conducted for other pollen types, such as oak and for a fungal spore allergen called Alternaria.

Real-time pollen monitoring means pollen grains are detected and counted by a machine connected to the internet and the data sent immediately out to the public. There are now several laser detection machines that are being trialled by scientists at the University of Worcester.

Hay fever and asthma sufferers can follow the pollen forecast, also known as the pollen count, to find out which pollen types are in season or coming along soon.

All of the UK’s pollen forecasts come from the University of Worcester, in association with the UK Met Office, and are produced by experts in the School of Science and Environment. More information on specific allergens can be found on our pollen forecast pages

Dr Beverley Adams-Groom works at The National Pollen and Aerobiology Research Unit in the School of Science and the Environment to monitor and provide the Pollen Forecast for the UK. If you are interested in the science behind the pollen forecast you may be interested in our science degrees. We also offer tours of our Pollen Labs as part of our Open Days.

All views expressed in this blog are the Academic’s own and do not represent the views, policies or opinions of the University of Worcester or any of its partners.